Intensity

July 30th, 2019Our eyes are amazing organs and can see a huge range of light intensities. A snow field on a bright sunny day is near one end of our visible range while a moonless, overcast night is at the other.

Light intensity is measured in candelas which is defined as the luminous power per unit solid angle emitted by a point light source. Whatever! To a non-physicist that probably doesn’t make much sense; as photographers how do we make sense of light intensity?

In photography light is measured in stops rather than candelas. A stop represents a halving or doubling of light. (I’ll discuss stops again in subsequent posts. For now I just want to introduce the concept.)

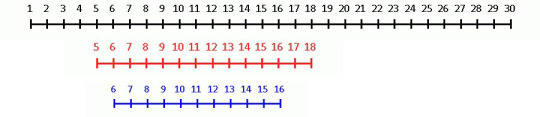

Measured in stops our visible range is about 30, which mathematically corresponds to a billion candelas since two to the thirtieth power is about a billion (2^30 = 1,073,741,824). In the graphic below our full visible range in stops is represented by the black number line.

We can see an incredible range of light intensities but not all at once. Our eyes adapt to the current intensity of ambient light but at any one time we can only see just under half the full range of 30 stops; or about 13 or 14 stops of light (represented by the red line in the graphic above).

Our ability to see a wide range of light intensities is referred to as ‘dynamic range’ and is controlled by our pupils which open or contract to allow an appropriate amount of light in. At any given time our eyes adjust to give us the most visibility by averaging the light intensity over a scene and adapting to that average. We might lose the brightest and/or darkest areas but we see the majority of the scene. If we move our focus to another region of the scene, perhaps to a darker zone, our eyes adapt by opening the pupil to allow more light to come in helping us to see in the darker areas but by doing so we lose visibility into the brighter regions.

Cameras work in a similar way to our eyes with the aperture acting like our pupil to control the amount of light reaching the film or sensor. But while our eyes can see about 13 stops of light, cameras can only see 10 or maybe 11 stops of light (represented by the blue line in the graphic above). (The better cameras on the market today can see about 10 or 11 stops of light; lower end cameras have a much more limited range and might only see 6 or 7 stops of light.)

If the dynamic range of light in a scene exceeds 13 stops, the brightest or darkest areas block out and we can’t see any detail in those areas. The same is true with a camera; areas in the scene that exceed the dynamic range of the sensor will block out and be rendered either white or black with no details.

This image was shot with my cell phone which has a limited dynamic range. The orientation is looking south with the sun just out of the frame. The bright sky was rendered completely white and the crack in the rocks below the back tire of my bike is completely black; both lack any detail whatsoever.

(LG G6, 1/800s, f/1.8, ISO 50)

For comparison, this next image was shot at the same time and location but this time looking northwest. In this image, with the sun at my back, the scene is more evenly lit and it has a narrower dynamic range; one that is within the abilities of the camera’s sensor. In this image the sky is rendered blue and the crack in the rock has some detail.

(LG G6, 1/640s, f/1.8, ISO 50)

Understanding the intensity of light and your camera’s abilities and limitations to capture that range of light is foundational. Using that knowledge to capture an image that conveys your mood and interpretation of the scene is what being a photographer is all about.