Shutter Speed

June 17th, 2025Shutter speed is the camera setting that controls the length of time that the film or sensor is exposed to light. Standard shutter speeds are: 1, ½, ¼, 1/8, 1/15, 1/30, 1/60, 1/125, 1/250, 1/500 and 1/1000 of a second. Like the standard aperture settings these values roughly correspond to a change of one stop of light between each adjacent value.

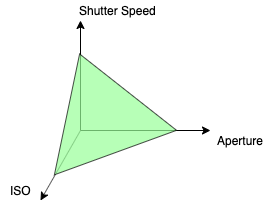

In my last post I presented the exposure triad (aperture, shutter speed and film speed) which I’ll get to soon but to start off I’m going to ignore film speed and just discuss aperture and shutter speed.

In the following graphic the shutter speed is represented on the vertical axis with long shutter speeds (1/2s) close to the bottom and short speeds (1/500s) toward the top. Aperture is depicted along the horizontal axis with small f-number (f/1.4, large aperture) toward the left side and large f-numbers (f/16, small apertures) on the right.

A properly exposed image is represented by the blue line which can be achieved using a variety of aperture/shutter speed combinations; two of which are show by the green and red dashed lines.

The green dashed lines represent a small f-stop (perhaps f/4) and a fast shutter speed (perhaps 1/125s) while the red dashed lines represent a large f-stop (perhaps f/11) and a slow shutter speed (perhaps 1/15s).

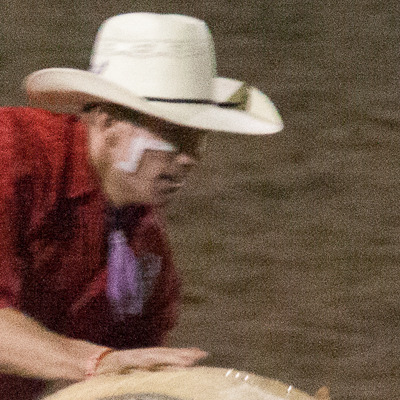

These two options will both result in a properly exposed image. In the first we have a small f-stop, i.e. large opening, that allows a lot of light into the lens (this is like filling the exposure cup with the faucet on full) which in turn requires a short shutter speed (to prevent the cup from overflowing). By comparison the other option uses a small opening (large f-stop) which allows only a trickle of light through the lens, therefore a longer shutter speed needs to be selected to allow sufficient light to pass through for full exposure.

These two combinations of settings will both produce similarly exposed images but will the images be the same? No, they won’t. As we discussed in previous posts the change in the aperture setting from f/4 to f/11 will provide significantly different depths of field.

So, which combination is correct? The answer is neither and both and it depends. It depends on what you, as the artist, consider most important to express as your vision.